Siemensstadt

16.3.22In west Berlin we cycle through Siemensstadt, a modernist model village of brightly coloured low-rise apartment blocks built in the 1920/30s for the workers of Siemens & Halske (S&H), now Siemens.

Built in the style of the Neues Bauen, or New Architecture movement by Der Ring collective of architects that included Walter Gropius, Otto Bartning and Hugo Häring, it provided dwellings of minimal size and standardised layout; and was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 20081.

Siemensstadt is considered an urban development phenomenon2 in that not only was it a new city built from scratch on undeveloped land, but it was conceived, planned and built by an industrial company for its employees.

Siemensstadt is considered an urban development phenomenon2 in that not only was it a new city built from scratch on undeveloped land, but it was conceived, planned and built by an industrial company for its employees.

S&H had started its first cable plant in 1899 and within ten years it employed 15,000 workers. Over the following decades its industrial complex grew exponentially, and the creation of the settlement meant workers no longer had to commute in from the city and surrounding areas by train, often in crushed conditions.

During the Cold War period, Siemensstadt was now on the outer edge of Allied-run West Berlin, surrounded by GDR-run East Germany and serviced by its S-Bahn4. West Berliners, unwilling to subsidise the regime in the East, boycotted this Siemensbahn service with new ‘solidarity’ tram and bus services that sprang up along the same route. This continued until 1980 when S-Bahn’s operator, no longer able to sustain the loss of millions running mostly empty trains through the west, closed the Siemensbahn - leaving the ghost stations that remain today.

1Siemensstadt Housing Estate. grandtourofmodernism.com

2Münzel, M. Siemensstadt: Building for the Future, from Journey through History. new.siemens.com 3Siemensstaadt oil painting (approx 1930) by Anton Scheuritzel.

4Siemensbahn. abandonedberlin.com

Checkpoint Alpha

13.3.22

On the drive to Berlin we stop off at Checkpoint Alpha, the former Cold War east/west border crossing. My research into settlements (as in villages, towns and cities) inevitably overlaps with issues of boundaries and borders. The division of Germany during that period continues to hold a powerful resonance, and never more than now with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The Cold War division of Germany1

The Cold War division of Germany1Originally opened in 1945 between the British and Soviet zones at Helmstedt/Marienborn, Checkpoint Alpha was in use until 1990. It marked the start of the 170km/110m fenced corridor section of the A2 autobahn (the blue line on the map above) which was the only permissable road approach through East Germany between West Germany and West Berlin.

Its checkpoint inspections were reportedly gruelling, after which travellers would continue along the sealed-off autobahn to Checkpoint Bravo at the outer edge of West Berlin. And if they arrived in under two hours they received a speeding ticket - an early form of the average speed check2.

1Map from the Memorial to the Division of Germany in Marienborn at Checkpoint Alpha.

2In case you were wondering... we complete the journey between Checkpoints Alpha and Bravo in 75mins.

Windowology

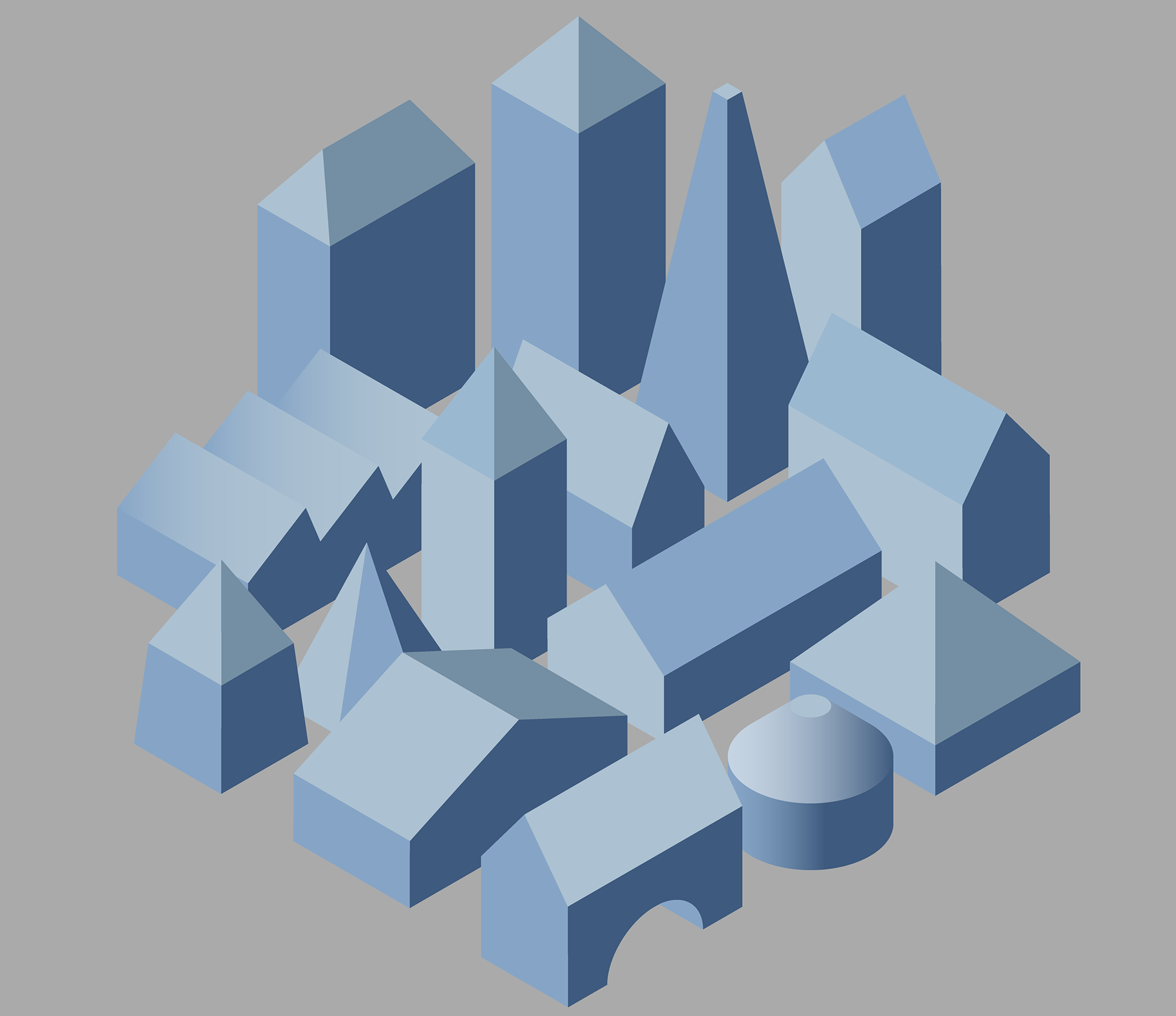

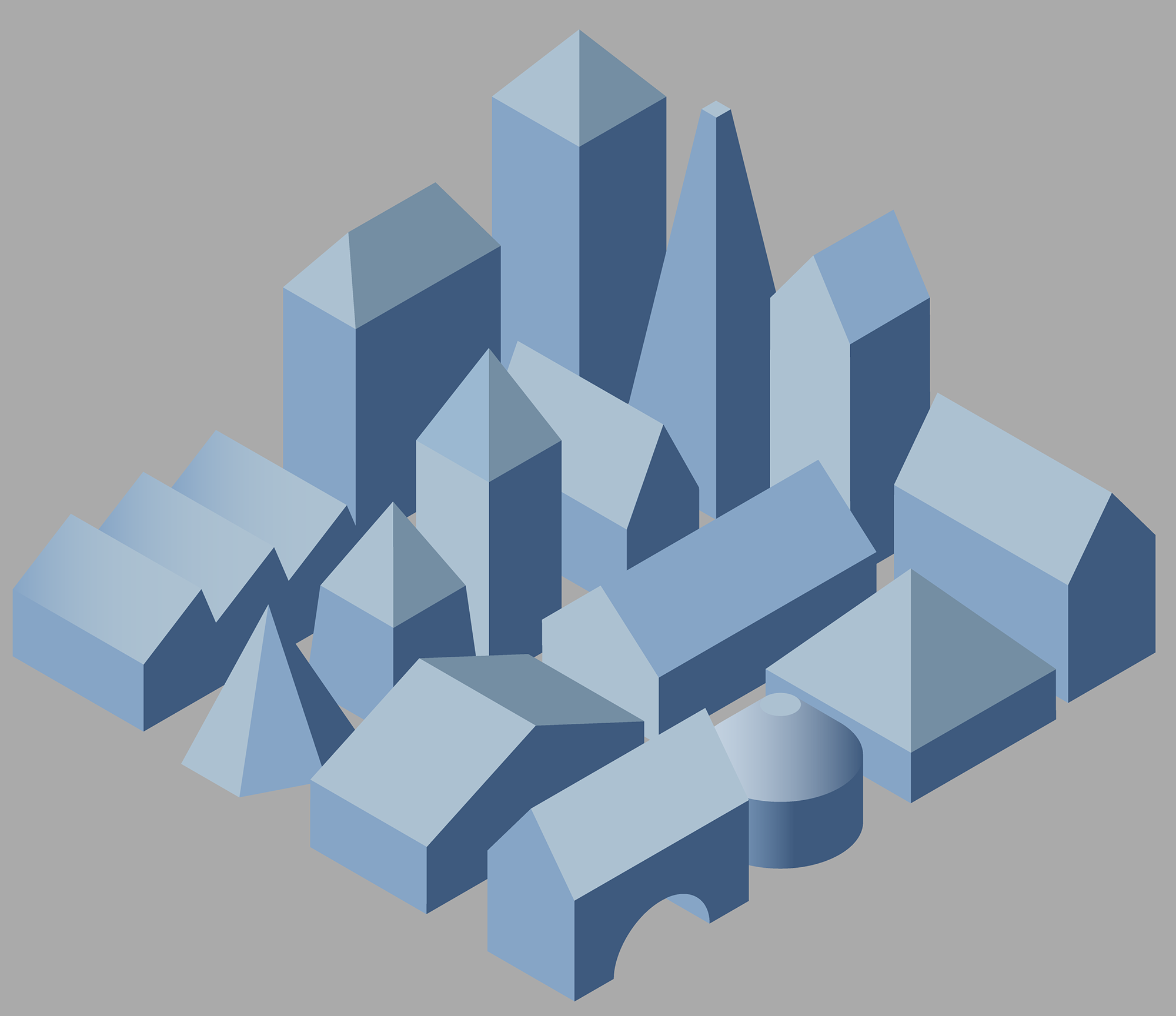

7.3.22My abstraction of building shapes for Model Village has involved a balance of stripping away as much detail as possible while retaining their recognisable proportions. Windows were an early element to be removed for they were also an unwanted indicator of scale. However, the need for patching with recycled denim has enabled me to use it as a form of suggesting the presence of windows.

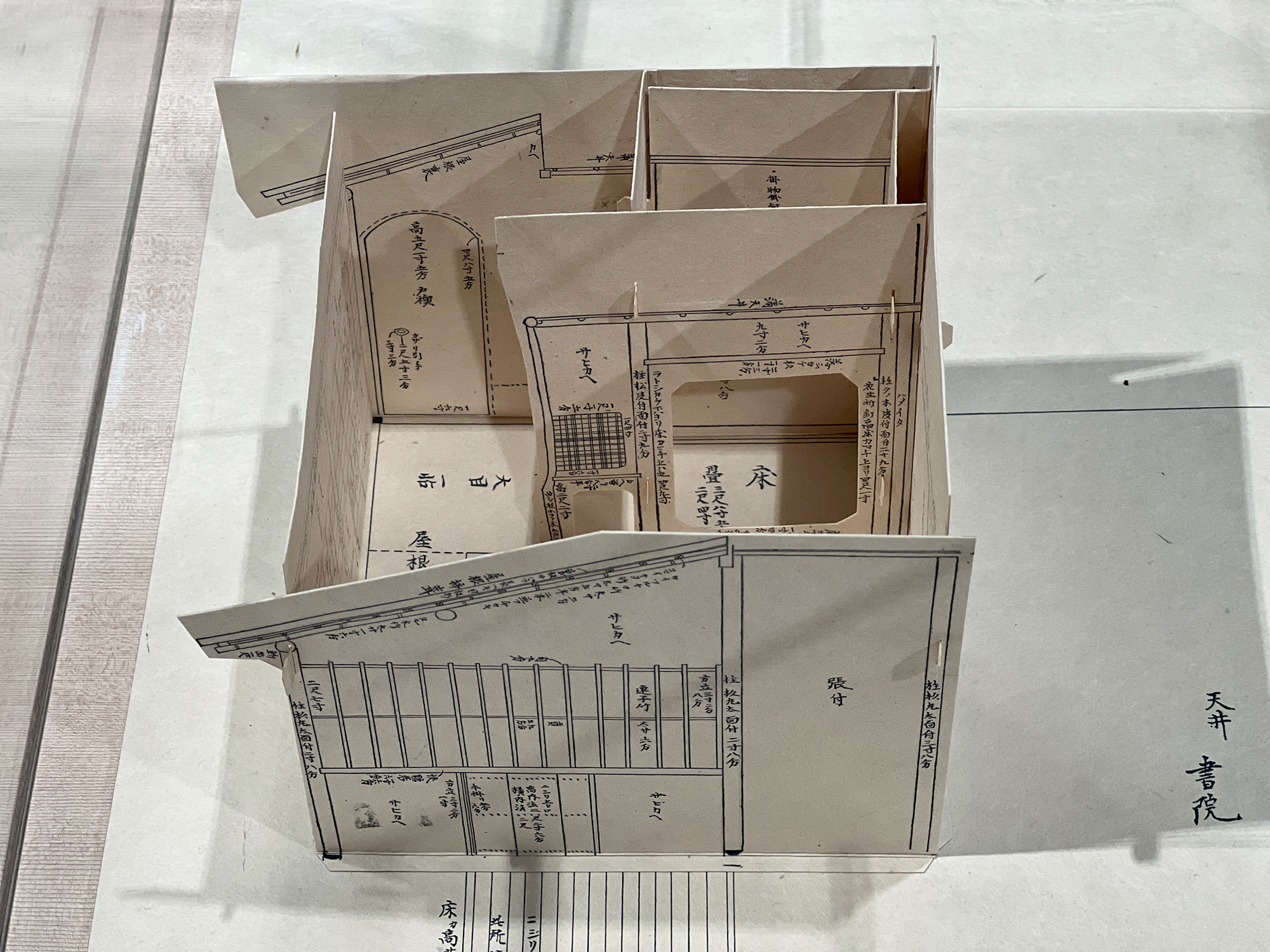

With this in mind I visit Windowology1 at Japan House, an exhibition described as one which explores windows as cultural objects2.

With this in mind I visit Windowology1 at Japan House, an exhibition described as one which explores windows as cultural objects2.

The exhibition compares the intrique of moveable windows and wall-less interiors found in Japanese architecture with those of other cultures in which windows are generally holes in masonry walls of stone and brick. Japanese teahouses, however, are conceived as closed boxes ‘punctured with an assortment of openings’4 and for this they hold a special place in Japanese culture.

Windowology’s centrepiece is a 1:1 scale 3D installation of the sketched design of a teahouse, surrounded by other smaller scale models.

It brings to mind my 2018 visit to the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, in which the 16th century Tai-an teahouse5, a national treasure, was on display. The height of its nijiri-guchi (wriggling-in entrance) was determined by the minimal space needed for a person to duck under, emphasizing the threshold between the outside and inside worlds.

It brings to mind my 2018 visit to the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, in which the 16th century Tai-an teahouse5, a national treasure, was on display. The height of its nijiri-guchi (wriggling-in entrance) was determined by the minimal space needed for a person to duck under, emphasizing the threshold between the outside and inside worlds.

Tai-an teahouse (1581) at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2018).

All pictures by P Hartley unless otherwise specified.

1The Windowology ehibition had been due to open in Spring 2020 but was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2Lekka Angelopoulou, S. (2020) Windowology Exhibition at Japan House Explores Windows as Cultural Objects in Architecture, designboom.com.

3Windowology picture by Takumi Oita Photography Co.

4Igarashi, T. (2022[2020]) Windowology: New Architectural Views from Japan, japanhouselondon.uk

5The Tai-an teahouse is from the Myōki-an temple in Yamazaki, Kyoto, and attributed to Sen-no-Rikyu).

Settlement Shapes

15.2.22

The arrangment of the soft buildings has inevitably led to discussions about the settlement’s outline shape. In the recent group photo it was arranged into a sort of rectangle grid; but as the Model Village grows I wonder if it should evolve into a looser, more organic shape.

In search of examples of irregular settlement shapes I look at those of UK cities1. Like all cities, their shapes and structures have evolved from, and are constrained by, their physical environment; and generally follow one or more basic patterns: geomorphic, radial, concentric, rectilinear and curvilinear.

UK city shapes and sizes: 1 London, 2 Leeds, 3 Sheffield, 4 Birmingham, 5 Edinburgh, 6 Glasgow, 7 Cardiff, 8 Manchester, 9 Liverpool, 10 Belfast, 11 Newcastle, 12 Bristol, 13 Nottingham.

However, as soon as I start to interrogate the shapes and sizes of UK cities I come up against the issue of which surrounding metropolitan areas to include in each city.

In response to this (and for the purposes of staying on track in this process blog) I use the shape of the cities defined by their core city authority areas. This means that the whole shape of greater London and Leeds appear here, but not so the other cities, which are generally ‘underbounded’. This refers to the fact that their core local authority areas with the name of the city do not reflect the true extent of their larger metropolitan areas1.

In response to this (and for the purposes of staying on track in this process blog) I use the shape of the cities defined by their core city authority areas. This means that the whole shape of greater London and Leeds appear here, but not so the other cities, which are generally ‘underbounded’. This refers to the fact that their core local authority areas with the name of the city do not reflect the true extent of their larger metropolitan areas1.

From Land Ground Earth Soil: the placing of walls in Islanders, the game about building island cities with limited space and resources2.

I am reminded here of the themes of boundaries and community edges that I explored in my film Land Ground Earth Soil (2019). Examples included gameplay clips from city-building games as well as conducting my own ‘Beating the Bounds’ of the London borough of Camden.

‘Beating the Bounds’ in Land Ground Earth Soil.

The beating of the bounds still takes place in some parishes today. Giles Fraser3 wonders if 'there is something Brexit-like about this ancient tradition', that globalisation has washed away so many of our familiar boundaries, many of us feel exposed and vulnerable without them. It is 'almost as if we needed to reassert a sense of place, to mark our connection to the land on which we live.'

He in turn quotes the evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar who famously argued that the human brain is capable of maintaining only around 150 stable relationships at any one time. This correlated with parish records showing that 150 was the average village size in the Domesday Book4 until later in the 18th century, before industrialisation.

The parish functioned then as a moral community. It looked after its own, raising local taxes to support and house the poor. The beating of the bounds was, as much as anything, a practical exercise in clarifying boundaries and determining who was responsible for whom.

In the spirit of beating the bounds, and in looking at my own connection to the land, my landscape, I embarked on my own perambulation for my MA project. I chose the bounds of the London borough of Camden as a secular equivalent, in which it exists to administrate and raise local taxes. Also because it is the area that I've had most engagement with.

Camden’s boundary is 28 km long, so the walk was divided into four sections that could comfortably be achieved over a series of Sunday mornings, with various walking companions joining along different sections of the route.

I wanted to observe this area I knew well with fresh eyes, to get a sense of its wholeness and to interrogate its seemingly arbitrary boundary lines. Walking through a landscape is, as Rebecca Solnit states, like the passage through a series of thoughts, 'A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape that was there all along, as though thinking were traveling rather than making.'5

He in turn quotes the evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar who famously argued that the human brain is capable of maintaining only around 150 stable relationships at any one time. This correlated with parish records showing that 150 was the average village size in the Domesday Book4 until later in the 18th century, before industrialisation.

The parish functioned then as a moral community. It looked after its own, raising local taxes to support and house the poor. The beating of the bounds was, as much as anything, a practical exercise in clarifying boundaries and determining who was responsible for whom.

In the spirit of beating the bounds, and in looking at my own connection to the land, my landscape, I embarked on my own perambulation for my MA project. I chose the bounds of the London borough of Camden as a secular equivalent, in which it exists to administrate and raise local taxes. Also because it is the area that I've had most engagement with.

Camden’s boundary is 28 km long, so the walk was divided into four sections that could comfortably be achieved over a series of Sunday mornings, with various walking companions joining along different sections of the route.

I wanted to observe this area I knew well with fresh eyes, to get a sense of its wholeness and to interrogate its seemingly arbitrary boundary lines. Walking through a landscape is, as Rebecca Solnit states, like the passage through a series of thoughts, 'A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape that was there all along, as though thinking were traveling rather than making.'5

1Rae, A. (2011) How Big is London? in undertheraedar.com.

Further reading: Burdett, R. (2015) ‘A Tale or four World Cities - London, Delhi, Tokyo and Bógota compared’ in Cities/Cities in Numbers, theguardian.com.

2Islanders (2019) Grizzly Games.

3Fraser, F. (2017) 'The parish is the perfect scale for moral community' in Loose Cannon/Brexit. theguardian.com.

4The Domesday book was the 'great survey' of peoples' holdings and their values in England and (parts of) Wales in 1086.

5Solnit, R. (2001) Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Penguin Books.

Further reading: Burdett, R. (2015) ‘A Tale or four World Cities - London, Delhi, Tokyo and Bógota compared’ in Cities/Cities in Numbers, theguardian.com.

2Islanders (2019) Grizzly Games.

3Fraser, F. (2017) 'The parish is the perfect scale for moral community' in Loose Cannon/Brexit. theguardian.com.

4The Domesday book was the 'great survey' of peoples' holdings and their values in England and (parts of) Wales in 1086.

5Solnit, R. (2001) Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Penguin Books.

Town Planning

6.2.22The first full set of sixteen denim buildings are now completed. They are quite bulky and I’m having to make shelf space to accommodate them. I am also now experimenting with their arrangement and how to exhibit them. Do I give them space, or jam them in together (like a skyline through a long lense)?

I lack the studio space to fully explore this right now, so for the purposes of the group photograph I opt for something in between: buildings with what look like alleyways (or ‘ginnels’) running between them.